Prague - Declassified files show that Karel Gott's psychiatrist in 1971 told the communist-era secret police, StB, that the pop music star suffered from a sexual deviation. The discovery of the interrogation transcript by Aktuálně.cz suggests that the regime may have used the information to blackmail Gott and to enforce his return to Czechoslovakia from West Germany, where he had emigrated shortly before.

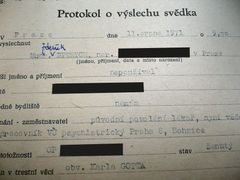

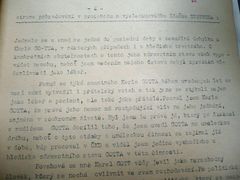

"Karel Gott suffered and probably still suffers from a sexual deviation," Zdeněk Dytrych told the secret police on 11 August 1971. He did not disclose the nature of the deviation, telling the interrogators that as a physician he was bound by confidentiality. Still, the psychiatrist added that Gott's condition had "a decisive influence on his actions, particularly in his private life". Dytrych told the agents that he had "introduced Gott to the artistic career ... which I considered to be the only solution from the point of his medical condition".

Gott says diagnosis was fake

Gott has now confirmed for Aktuálně.cz that he was Dytrych's patient and friend in the 1950s, before he became a professional singer and while he worked as an electrician at ČKD.

"I sought his advice on certain issues of mainly personal nature," says Gott.

He insists that he and Dytrych agreed on a fake psychiatric diagnosis that would help Gott leave his job and start a career as a singer.

"After the state paid for your apprentice training, you were not allowed to quit the factory for some time. This was the only way to do it."

Dytrych is no longer alive and it is impossible to tell why he testified the way he did. StB files show that he was registered as an StB agent, acting under codenames Petr and Tantal-1.

Cyril Höschl, director of a psychiatric clinic where Dytrych worked before his death, says:

"[Dytrych] loved beautiful and big cars; he admired America in all its aspects and tried to reconcile these passions with the life reality of the 1970s Czechoslovakia, which was not always easy."

Gott says he does not mind that Dytrych revealed his diagnosis to the interrogators. He insists it was fake and the secret police never used it against him. "They did not blackmail me; they never wanted anything," says the singer. "They showed no interest in me. I didn't dance with that lot."

Dytrych and about 20 other friends and relatives were interrogated in 1971 after Gott failed to return from a trip in the West, which was regarded as an act of defection. The singer claims he has never seen his file nor Dytrych's testimony.

"I haven't seen the file. I fear that if I take a look I will lose all illusions."

Collaborator, or rebel?

The discovery of the StB file adds to earlier speculations that the regime used sensitive information against Gott. Former Czechoslovak spy Josef Frolík, who in 1969 defected and worked for the US and UK intelligence services, told the US Senate in 1975: "The popular Czechoslovak singer Karel Gott is an StB agent, recruited in 1960 with the help of compromising information (he had been convicted of exhibitionism)."

It remains unclear whether Gott in any way collaborated with the communist regime. He returned from the West in the autumn of 1971 after the Czechoslovak leader Gustáv Husák promised Gott would not be prosecuted for his attempted defection and would be able to go on with his singing, including international tours. There is no direct evidence that Gott had to promise something in return.

In 1977, the idol of the state-controlled show business industry signed the Anticharta, a petition opposing Václav Havel's Charter 77. Many celebrities joined the Anticharta out of fear they would otherwise be banned from the limelight. Later in the year, Husák decorated Gott with the title of an Artist of Merit; in 1985 Gott was the first pop singer named a National Artist, a title previously reserved for serious arts.

Gott occasionally showed signs of political disobedience. He included some banned songs by Jiří Suchý on one of his albums, and asked Suchý to christen it, although this meant the state-run television refused to broadcast the event. The communist-era files include a report on an incident at Prague Airport in which Gott verbally attacked a man wearing a Lenin badge. The singer chided the man for associating himself with a country that had invaded Czechoslovakia with tanks in 1968.

Finally, in January 1989 Gott refused to publicly denounce anti-regime demonstrations held during the anniversary of Jan Palach's self-immolation. In November of the same year, when it was not yet clear whether the regime would fold, he sang the Czech anthem at an anti-regime rally on Prague's Wenceslas Square, an act of disobedience that other singers shrank away from.