Gypsy music in Prague

Po Po Café Petl Gitans plays every Sunday night, starting from 9 p.m.

Latin Art Café Ibsulon plays gypsy music every Saturday night, starting from 8 p.m..

Krasny Zraty Sporadic. Different bands. Ask ahead.

The Cemetary between Zelivsheho and Biocupcova, Zizkov Maybe it's creepy. But mid-morning and early afternoons on Sunday, there are often Roma funerals here with hauntingly beautiful music, if you can manage to keep a distance.

Rubin Random, sometimes, not always, no guarantee…just ask them.

Prague - Romale, chavale. Imar hin tosarla. Romale, chavale. Imar hin tosarla. Tosarla, tosarla, tosarla. E masina imar dzal, palo svetos roma phiren. Tosarla, tosarla, phiren. Phiren, phiren, phiren."

(Roma people, white people. The sun is rising for us. Roma people, white people, the sun is rising for us. Rising, rising, rising. The train is coming. Roma travel through the world. The sun is rising for us, rising. They travel, travel, travel).

The first time I heard these lyrics was in Strasnicke Divadlo, somewhere on the outskirts of Prague. A French accordion player friend, Mathieu Gautron, invited me to see a band called Cilagos, though until the day of the show he still was not certain they were going to show up.

"I am never sure if they will come until I really see them, because they do what they want," he told me.

The hypnotically gorgeous music that night, with its smooth chromatics and strong, sharp harmonies put me in a trance. There were three accordions, two violins, four guitars, and about 20 women belting. I was left wanting more.

And they gave it to me.

Afterwards, we sat around drinking vodka in a makeshift bar attached to the theater as the music swelled into the early morning hours. Gautron was the only gadje, or white person, playing music. Gadje is a Roma word for anyone non-Roma. Gypsy is a non-Roma word widely used to describe the Roma, although in Europe the word is sometimes viewed as pejorative, or slang.

"He is the only gadje who can play our music with us," said one of the Cilagos members.

I asked Gautron where and how I could learn to sing gypsy music. He told me that the only way to do it would be to find a group of gypsy musicians, hope that they liked me (which would be highly unlikely, considering my gadje status and lack of language skills), and get completely wasted with them. That's what he did with Cilagos when he first met them three years ago in Nachod, a small Czech village on the Polish border. Then, and only then, would I have a shot at becoming a gypsy musician.

The outlook was grim.

I asked Gautron where I could find more gigs to watch.

"It's very hard because it changes all the time. You need to know the musicians," he explained.

I found them at Latin Art Café, a cozy little hideaway in Prague's Mala Strana quarter. The sign said something about gypsy music on Saturday nights, so I investigated.

The sounds of Roma lyrics wafted into the air. Inside, I found Ibulon. The band's singer/guitar player, Jakob Xavier Baro, had rough, raspy vocals and precise chromatic riffs. He meant every note he sang.

I found out that he was not Romani, but half Czech and half Slovakian. He grew up in Domazlice, a small town in West Bohemia located about 100 miles from Prague. He grew up with gypsies and spent every day with them.

"We were good friends and had many fights together," explained Baro. He remembers hearing them sing inside their home and fell in love with the atmosphere.

He attended workshops through a Czech program known as The International School of the Human Voice where he learned about the different spectrums and varieties of gypsy music over four years. Since then, he has played with a plethora of gypsy musicians.

I'm obviously not the only white kid who has become swept up in the mystical wonder and exoticism of gypsy music, wishing I could be a cultural chameleon. It seems like there are a lot of us. Still, I wondered where the legit gypsies who would actually talk to me were.

Baro, a starving artist if I'd ever seen one, needed some food. Myself, a starving art-less soul, needed some gypsy music lessons. So we traded stomach food for soul food, and I started learning traditional gypsy music from a white guy. We spent entire nights singing in that little café, and continuing to belt out our gypsy anthems as we crossed the Charles Bridge against the backdrop of the morning sun. I was in Roma heaven.

I devoured gypsy music— Vera Bila, Gypsy Kings— I saw real gypsy bands play in little pubs, but could do little more than stare in awe.

I asked Baro if he could introduce me to real gypsies. He said he would, but in the meantime, I asked around to see what it is that makes us gadjes so fascinated by gypsies. I spoke to Baro's friend Byron Asher, a clarinet player from Maryland who came to Prague to try to make it as a musician and learn about gypsy music. He had heard an experimental gypsy clarinetist once at home, and it seemed exotic and "freer" than jazz.

"No one wants to dance to jazz anymore. I don't wanna spend my time playing for an old white cigar-smoking audience. When we play gypsy music, everyone dances."

We marveled together for a few minutes and mused over gypsies and learning their music.

"My dream," he said emphatically, "is to join a gypsy caravan—even though they're pretty rare now-and sit around with a bunch of old gypsy men all day jamming and drinking whiskey. I would just find these people, and keep going to play with them over and over until they couldn't refuse me anymore."

He's got the right idea.

Both Baro and Gautron told me that singing with gypsies was about having a powerful connection, "like family," but also that gypsy musicians were difficult to play with and could be unreliable. Generally, they don't like to play with or talk to white people, probably in part due to the extreme racism directed at them. The Roma minorities both in the Czech Republic and across Europe face severe social problems such as unemployment, drugs, and substandard housing - and are often perceived as outsiders.

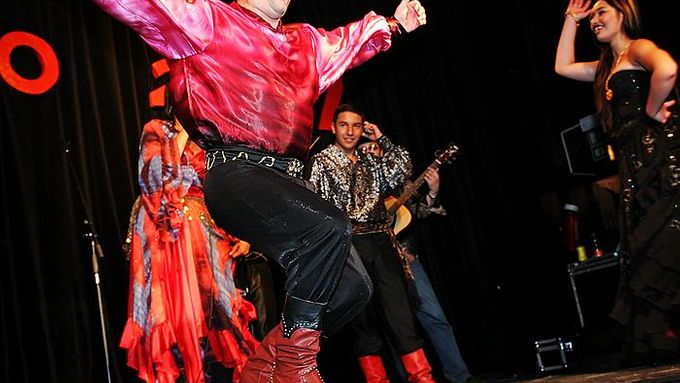

Baro finally agreed to translate some questions for one of the members of Gitans, a modern gypsy band who plays weekly at Po Po Café Petl. A stoic bassist, a goofy guitar player with a fun, high-pitched voice, an extremely large drummer with a booming voice and wide eyes, an electric violinist with chiseled features and a sly way of locking eyes with every female in attendance, and a quirky keyboard player who stared out into space—all of them singing.

When they suddenly launched from modern music into something more traditional-sounding, the area around the stage was flooded with dancing women who came out of the woodwork. At the table closest to the stage were seated a group of dark men, smoking cigarettes, drinking, and staring at the stage. They conjured up images of some sort of Roma mob. When the band took a set break, they sat with these bodyguards as I remained perched in my corner.

Finally, Baro arrived and told me that the violinist would answer some of my questions. His name was Josef Senki, and though he's 19, he looked like he's at least 30 with his expressive eyebrows, piercing eyes, and full lips. He'd been playing the violin since he was three-years-old, and learned everything from his grandfather. He noted the importance of gypsy music as being part of preserving the culture.

"Many gypsies," he said, "don't even really speak gypsy. They want to be someone else."

There are several branches of the Romani language that have been formed since what some ethnologists say was their migration to Europe from medieval India. As a nomadic people, preservation of Romani culture has been highly dependent on oral tradition, making music a key factor in keeping it alive.

Senki attends a music conservatory in Prague and plays with another band, Bengas. I asked him if he minded playing with gadjes, and he shrugged.

Then he said something to Baro and cut our interview short.

I asked Baro what happened, and he also shrugged. "He was bored to sit here with a beautiful girl, and me in the middle translating some questions. He was bored. So he left."

Ah.

So, he introduced me to Pavlina Matiova, a 20-year-old Roma singer and pianist from Prague.

"She's good," he told me. "If you tell her to practice at four, she is there two minutes early."

We sat down and she was immediately receptive, eyes wide with excitement.

She came from a musical family and was playing music before she could even speak. She also studies theater.

"I'm so stupid because I need to be a comic. And I need to be pianist. And I need to be a singer. And I need to study teaching, so I can be a music teacher. I want to do everything," Matiova said. She also sings in a gypsy choir: Ikalarove Romano Rat and Apsora.

Matiova is happy with the growing attention to gypsy music, but also noted that it is still very difficult to make a living from it.

She loves that white people want to sing gypsy music. She said that music is a language for everyone to speak together, and that gypsies often sing covers of other music so it's a good cultural exchange. I asked her how I could learn and, laughing, she said, "find a gypsy boyfriend."

And the next leg of my Roma-romance-music-mission began.

This story was originally published by the Prague Wanderer, a web-zine run by New York University students in Prague, Czech Republic.

Lia Tamborra is a fourth-year student at New York University studying theater. A version of this article was originally written for the Travel Writing class at New York University in Prague.