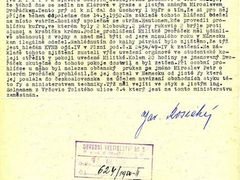

Prague - The Czech Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes (ÚSTR) has brought an unexpected twist to the life of Czech-born writer Milan Kundera. A 1950 police report discovered by the institute quotes Kundera as informing the police about the whereabouts of Miroslav Dvořáček, a Czech émigré working as a spy for the West.

According to the record, Kundera, then a student at Prague's Academy of Performing Arts, told the police a suspicious person had stored his suitcase with Kundera's fellow student Iva Militká. Kundera had learned about Dvořáček from Militká's boyfriend and future husband Miroslav Dlask. Dvořáček was arrested and spent 13 years in jail and work camps.

The story was broken on Monday by the weekly Respekt. A day later, the ÚSTR confirmed the police report cited by the weekly was genuine, and provided additional evidence.

In an interview for Aktuálně.cz, Iva Militká-Dlasková (79) says the discovery of the document only confirms what she has known since the 1990s. Before his death, Dlask broke his 40-year silence about the case and told his wife he had told Kundera about Dvořáček before the arrest.

Dlask was the only person whom Militká took into confidence about Dvořáček's suitcase. For the following decades she was convinced that it was her husband who had tipped off the police.

"I asked my husband many times what exactly had happened, but he would never answer," says Militká-Dlasková. "He told me about Kundera only in the 1990s, after we retired."

Militká-Dlasková excuses Kundera for his role in the case. She hopes the new evidence will persuade her former friend Dvořáček, who now lives in Sweden and has always believed he was betrayed by Militká herself.

Earlier this week Kundera himself denied he had been the informer.

I destroyed his whole life

For a long time you lived with the thought that your husband had betrayed your friend. Now you have learned it was otherwise. Has the revelation relieved you in any way?

Actually, it hasn't helped me at all. I don't give a damn about Kundera. I would like to know what reason my husband had to tell him. And I still don't know.

What do you care about, then, if not about Kundera?

I would like Mirda [Dvořáček] to believe that it wasn't me who reported him.

What do you think about Kundera's statement saying it's all lies?

The documents seem genuine to me. It's possible that Kundera doesn't remember any more, since it's been 60 years and he didn't know Mirda personally. I'm not sure that he knew what would happen. I don't like the fuss surrounding the case today. People make mistakes when they are young. So did I, and I haven't forgotten.

Do you regret telling your partner about Dvořáček?

Yes, I do. Mirda's father was seriously ill all those years. Mirda himself went to jail and his younger brother fled to Canada where he and his children drowned. The Dvořáček family had a very hard life.

Did you follow Dvořáček's trial?

I didn't. I only heard from my parents. There was talk about it in Kostelec.

You weren't interested?

I knew that he was facing a life sentence and that in the end they slightly reduced the sentence.

Have you ever tried to contact Mr Dvořáček or his family?

I have never done that. I was afraid of their reaction. After all, what was I supposed to tell him? Forgive me? How could he - I destroyed his whole life, no matter how unintentional it was.

Publicity hasn't helped

Why have you now decided to speak up about an event that happened so long ago?

There have been several impulses. In the spring I learned that Mirda lives in Sweden. I was just writing a memoir in which I mentioned the case. When my grandson Matěj learned about it, he asked me whether I would like to find out what exactly had happened. I told him I would. I wanted the truth to be saved somewhere for posterity. I regret that the findings have been publicized.

Why do you regret it?

I still don't know why my fiancé went to confide in Kundera. The new findings have not persuaded Mirda, guessing from his first reactions, and people in my hometown, Kostelec nad Orlicí, who I care about are mostly no longer alive. So in that sense the revelation hasn't helped.

What can be so wrong about the information being publicized?

I don't like the whole fuss about it. It makes my sister uncomfortable. My best friend has told me she was offended. And it hasn't helped me. On the contrary, the once forgotten past has resurfaced again. People will skim the story and think, this Militká must have had a finger in the pie. And I did - but why should people know if it's not their business, at all?

Relief after 40 years

When did you find out that your husband had told Kundera about Dvořáček?

In the early 1990s I told him again I would like to know what exactly had happened. And he wouldn't tell me anything specific again, except that he had told Kundera.

What did it mean for you, knowing that Kundera had been involved?

It gave me some relief, knowing that it wasn't my husband who went to the police. Although he might have asked Kundera to do that. Or he might have just turned to Kundera for advice because he didn't know what to do.

Why didn't Dlask speak about Kundera much earlier? It must have been difficult to live with the thought that everyone took him for an informer.

I don't know - we never talked about that.

Have you read Kundera's books?

I've only read Laughable Loves - and then the Joke, which I didn't like. I also started reading The Unbearable Lightness of Being but that one somehow didn't work for me. The Loves were great, though. That's also why I think the new revelations are not so important. He was 20 then.

But he wasn't stupid. He must have known what consequences his report would have.

Maybe he cared about Tása [Miroslav Dlask] and did it for him. But I wasn't aware that they were great friends. I think they didn't have any contact after that.

Why do you think you were not held responsible after the arrest? People used to go to jail for trifles and you invited a spy to sleep in your room.

I had no clue he was a spy. Kundera only reported that an acquaintance had left a suitcase in my room, but not that he would sleep there. I think I wasn't involved at all, and that's why nothing happened to me. I wasn't interrogated once in my whole life and there is no file on me. It is possible that Tása urged Kundera to make sure I would come off unharmed.