Prague - A small town Čierna nad Tisou´s freight train station has always been a busy place where trains come, download and load and go again.

One day this little town of 4,000 at the Czechoslovak-Soviet border saw a breathtaking scene that has changed the course of Czechoslovakia´s politics.

In 29 July 1968, Soviet political representatives arrived in Čierna nad Tisou to meet their Czechoslovak counterparts.

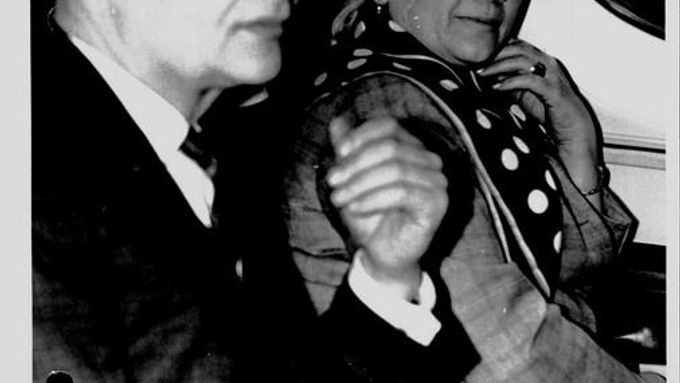

The meeting between Secretary General of the Czechoslovak Communist Party (KSČ) Alexander Dubček and his Soviet counterpart Leonid Brezhnev took place at the railway station, in a specially prepared train, made in the USSR.

The talks took place in a nervous atmosphere, with tension hanging in the air. But it was probably in Čierna nad Tisou that the Soviets decided to invade Czechoslovakia in order to halt the reform process spearheaded by Dubček.

Read more: ID pierced by bullet a reminder of 1968 invasion

Why Čierna nad Tisou?

A compromise had to be made when choosing the place for the meeting. Dubček favored Košice, a major Slovak city near the border with then Soviet Union, while Brezhnev proposed Lovov, a city in the western part of Ukraine, which was then part of the Soviet Union.

The small town of Čierna nad Tisou offered no facilities suitable for hosting a high-profile political meeting, so the Soviets decided to host the meeting in their train. Every night they crossed the border to Uzhgorod, a city at the border with Ukraine and near the border with Hungary.

Reform wing

The meeting lasted four days during which Dubček was asked to remove some politicians from the leadership of the KSČ, who were seen as unwanted by the Soviet Union. It was namely Josef Smrkovský and František Kriegel.

Josef Smrkovský was in the reform wing of the Communist Party and he is famous for his anti-Soviet feelings. "If someone thinks we are controlled by the Soviets, they are badly off base," said Josef Smrkovský in the summer of 1968.

František Kriegel, member of the Prague Spring reform wing, was the only one who refused to sign the Moscow Protocol in 1968. In 1977, he was one of the first signatories of the human rights document called Charter 77.

The Soviets also asked Dubček to disband Czechoslovak organizations viewed as anti-socialist by the Soviets; it was for example the Club of Committed Non-Party Members (Klub angažovaných nestraníků, KAN) or K231, an association of political prisoners from the 1950s.

Freedom of (anti-Soviet) speech

Leonid Brezhnev had sharp words for the freedom of speech that prevailed in Czechoslovak media at that time. It allowed Czechoslovak journalists to voice scathing criticism of the Soviet Union. He was especially infuriated with a caricature of him, published in the Reportér weekly.

The USSR then justified the Warsaw Pact invasion to Czechoslovakia on 21 August 1968 by claiming that Czechoslovakia didn’t fulfill its obligations both sides allegedly agreed on in Čierná nad Tisou.

Read more: Human torch of 39 years ago strongly remembered

In 12 August, Brezhnev complained to Dubček during a phone call that Czechoslovak media continue in their attacks against the Soviet Union. “As regards Czechoslovak mass information organs, they continue unhampered in their attacks against the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, against the Soviet Union, and they even insult top representatives of our party. They call us Stalinists, and so on. I want to know, what does it actually mean?” said Brezhnev then.

Train revisited

The meeting in Čierná nad Tisou was not the first occasion in which a key debate changing the course of international politics took place in a train.

In November 1918, after its losing the First World War, Germany signed an armistice in a railway carriage in Compiègne Forest, France.